Schoolmaster pals died on the Somme

Two of Shrewsbury School's masters, Evelyn Southwell and Malcolm White - both sent to the front - exchanged letters before they were both killed in the battle of the Somme.

Their collection was published in 1919 as "Two Men; a memoir".

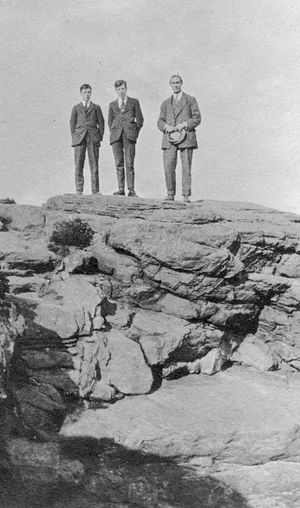

Southwell had graduated from Magdalen College, Oxford, and rowed for the university crew and even as a 'spare man' in the Olympics in 1908 before starting at Shrewsbury in 1910, aged 24. White, who joined the school the same year, aged 23, was a Cambridge graduate and talented violinist and singer. They were such close friends that colleagues knew them simply as 'the Men'.

When it became clear that White would be called up, he wrote, in a letter: "The only thing I am really afraid of is that I shall be afraid."

He wrote of his great friend: "Evelyn's soldiering is one of the finest sacrifices of this war, undertaken in spite of his characteristic distaste for all, or a great deal, that it involves."

Their letters recall the day to day life in the dugouts – which they created themselves in six-hour stretches of constant digging – and the 'monosyllabic rifles and chattering machine guns' (White) the rain and the mud.

They were unable to organise postings together, but corresponded until White's death, on July 1, 1916, in an attack near the village of Mailly-Maillet in the Battle of the Somme. White's last words in his diary on June 29, were: "We go up this afternoon, and this book must not go too."

In his last letter to Southwell, written knowing he was about to go over the top, he described himself as feeling like a coach before the (rowing) Bumping Races, adding: "Our new house and Shrewsbury are immortal, which is a great comfort".

Knowing he might not make it, he wrote to his family: "It is…a great comfort to think of you all going on, living the same happy lives that we have led together, and of the new generation coming into it all." He said his death would make up for small acts of selfishness in his life.

White went ahead of his men and was hit first. He told his men: "I'm all right; go on.' At that moment a shell burst near them and White was never seen again.

Three days later, Southwell addressed a letter to his old school house, remarking: "I am in great anxiety about our Man; though I can't say where he is or what he is doing."

Southwell only learned that White was missing in the second week of July. He wrote in anguish to his mother of his friend's death: "I have faced the casualty list daily without a tremor for two years now, and now, when I am hard hit myself, I cry out! Mum he was such a dear; he was so keen on everything, and the most true 'artist' in the full sense, that I have ever known.".

Southwell was killed himself by sniper fire on September 16, near Delville Wood. A fellow officer who survived the pus,h describing it as truly 'unpleasant', said Southwell had been 'magnificent' throughout: "If he knew what fear was, he never shewed it (sic)".

Another assistant master who was killed in 1916 was Leslie Woodroffe, 31, who was awarded the Military Cross for gallantry. Before his death he wrote vivid portrayals of life on the front line in letters published in the school magazine.

He wrote comically about conditions in the trenches, presumably to spare the feelings of those back home: "Please do not imagine our troglodyte life to be one of hardship. We bask in the sun (when we are not being shelled) and our menus would rival those of the Ritz. All the same, I look forward to returning."

He revealed that everyone was in 'holy terror' of German artillery fire: "You simply cannot imagine the din it makes; shells simply scream as they go over your head and when our big guns go off, the place simply quakes."

Of the 'Jack Johnsons' (16" howitzers) which he could hear whizzing a mile off, Woodroffe said: "You see a dense black column rise into the air about the height of a house, closely followed by the loudest roar you can imagine".

By day, it was 'suicide to show yourself' on account of the snipers, which he described as 'a perfect pest', adding 'a single man caused more bother than any number of Germans in trenches'. In the daytime, he revealed 'we simply eat, sleep, smoke and sit very tight'.

Woodroffe believed the Jack Johnsons should be barred after the war, since 'the mere concussion alone will kill a man, so that they won't give you a sporting chance'.

Woodroffe was one of three brothers. All had been head boys at Marlborough, all were in the Rifle Brigade and all were killed. His younger brother Sidney was awarded the Victoria Cross, posthumously, for his actions on July 30, 1915 at Hooge, in Flanders Belgium, when his position was heavily attacked with bombs.

This letter called THE SHELLS was written by White to JM West, on April 22, 1916

"I will describe the various shells and my attitude to them:

(i) The Whizz-bang; which comes from a field-gun, close up to the enemy's front line, and is generally shrapnel. This bursts almost before you know it is coming, so that there is no time to feel frightened.

ii) Our own; which one hears whistling through the air all the way, from the report of the gun to the explosion near the enemy's lines. One knows roughly where they are, and there is nothing to excite more than a mild interest.

(iii) The enemy's big-gun and howitzer shells. These, especially the latter, can be heard whistling for some time, and one can tell if they are coming in one's direction or not. These have affected me unpleasantly; a series of them came over, and one hit our trench one day. It was not very alarming, because I was in bed in my dugout at the time. Still, I did just feel as I heard them coming that it might be serious, and felt like saying, ' For goodness' sake burst, and tell me where you are '."

*(BLOB) All pictures courtesy of Shrewsbury School archives.