Shrewsbury prison governor appearing in new ITV reality show

Young offenders being turned out of their beds at dawn, a brisk work-out before breakfast. Hard labour chopping logs throughout the day, and a strict lights-out at 9.30pm in the evening.

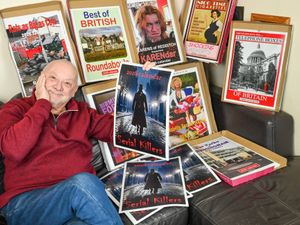

Gerry Hendry, who has a starring role in ITV's new reality television series Bring Back Borstal, believes there was much that was good in the way the penal system dealt with young offenders in the 1930s.

The former governor of Shrewsbury's Dana prison, who will be seen over the coming weeks as the stern housemaster instilling some old-school discipline into an assortment of young miscreants, believes there are few people who cannot be rehabilitated if they are given the right level of attention. But he believes that for this to work there needs to be a lot of attention focused on the individual, not to mention a great deal of tough love.

While the focus is on the regime of the 1930s, Mr Hendry used a decidedly modern expression when he was introduced to viewers in last night's programme.

"You need to man up," he told the aimless, slovenly young bunch slouched in their dormitory, setting the tone for four episodes of bust-ups, tears, and the occasional flicker of emotion when the wrong 'uns start to see the error of their ways.

"Prisoners like it when they have rules laid down for them," says Mr Hendry.

"They like it when they understand clear rules and guidelines, they understand acceptable behaviour. It's when people keep moving the line in the sand and changing the rules all the time that you have problems."

The 12 youngsters who appeared at the start of last night's programme had more than 60 convictions between them, and most of them had experience of one form of custody or another. But the regime proved too tough for four of the youngsters who quit the camp by the end of the opening show, with some of them deciding to accept more conventional forms of punishment instead.

"They were all volunteers," says Mr Hendry. "We couldn't make them do it."

Had those taking part not been volunteers, and had Mr Hendry and borstal 'governor' David Wilson had the power to keep them inside, does he believe they might have benefited?

"That's a very good question, and I will leave it to the viewers to decide," he says.

But he is a firm believer that most prisoners can be rehabilitated.

"I believe there are a handful of people who will never change, people who are, I suppose, evil, but I have also worked with a number of very nice prisoners, who, but for the grace of God, are just like you or me, and we should always remember that."

And he says offenders are, in many respects not that different from most young people.

"It is difficult for youngsters from any walk of life to grow up without firm boundaries," he says. "If they have no clear boundaries when growing up, how are they going to understand the rules of society?"

Mr Hendry, who was in charge of Shrewsbury prison for eight years prior to its closure in 2013, is proud of the work the institution did in rehabilitating offenders, particularly with the links built up with local industry to find offenders jobs on their release.

But he is critical of prison regimes which leave inmates locked up for hours on end.

"One of the lads in the series said when he was in jail all he did was watch television in his cell and ate," he says.

"In the series you see them being woken up at six in the morning, doing PE before breakfast, having sensible meals, going to work in the community and getting an education. There is no television and no games, and no lying on your bed all day."

He stresses that the 1930s-style discipline shown in the series should not be confused with the 1970s portrayal of borstal life as depicted in the controversial television play Scum, which provoked a fury from Shropshire campaigner Mary Whitehouse. The play, which starred a young Ray Winstone as borstal 'daddy' Carlin, depicted a brutal regime of casual violence, brutal rape, and staff indifference.

However, in its early days, the borstal system was loosely modelled on Britain's elite public schools — only with stronger locks.

While Mr Hendry does not go so far as to suggest that the clock can realistically be turned back 80 years, he points out that of those who passed through the borstal system in the 1930s, only 30 per cent of them went on to reoffend.

"That compares to around 80 per cent today," he says.

Many will see the regime portrayed in Bring Back Borstal as reminiscent of the 'short, sharp, shock' detention centres introduced by former Home Secretary William Whitelaw in 1982. While the images of the brisk, boot-camp style institutions played well with the general public, they did not find favour with the judiciary, who preferred to pass longer sentences in what they perceived as being more humane and enlightened environments.

"The trouble with the short, sharp shock was that it was too long," says Mr Hendry.

"A short, sharp shock would be to frighten them, to show young people what it is like, that it isn't very nice, but that there is another way."

Rob Allen, co-founder of the Justice and Prisons campaign group, has dubbed the ITV series 'punishment porn', and says it is unrealistic to compare reoffending rates between 1930s borstal training, which targeted offenders thought to be most likely to benefit, and today's young offenders' institution which take criminals from all backgrounds.

"Borstal training was always one of several custodial sentencing options designed for those individuals deemed most likely to respond to the training on offer," he says.

"Comparing the success rate to the failure rate in today's institutions which take all-comers, is looking at apples and oranges."

Mr Hendry says that the courts have always had a wide range of measures at their disposal.

He says one important difference is that prisoners respond better to individual attention, rather than simply incarcerating them for a while.

"It's all about investing time in them," he says.

"That doesn't mean to say it costs a lot of money, investing in a person isn't about throwing lots of money at them, and it's not about meeting government targets and getting the right tick in the right box.

"But if you have got prisoners who are just locked up all day doing nothing, how is that going to help them re-integrate back into society?

"Reoffending by criminals when they come out of prison costs the country £11 billion a year, and that's just people who have been discharged from prison.

"Look at how that money could be spent on other things if we invested a little time in people."