Were Iron Age Salopians the first Eurosceptics? What life was like at ancient Wrekin hillfort

Shropshire is packed full of history and mystery, from Roman towns to missing Medieval villages, but very few locations are as intriguing as The Wrekin's famous Iron Age hillfort.

Most Salopians with an interest in the distant past will know the area was probably once inhabited by a tribal group called, by the Romans, the Cornovii.

But what was life actually like for these people, and how did their activity thousands of years ago shape the landscape in a way that's still visible today?

The answer, according to an expert on the subject, is not what you're expecting.

Ancient earthworks, like those at the Wrekin's summit, are often associated with the idea of rough-and-ready tribesmen armed with primitive tools and violent tendencies, but for those who lived on and around The Wrekin during the later centuries BCE, the whole barbarian image might be a bit of a fallacy.

According to Dr George Nash of Liverpool University, if we want to understand what life was like for these people, it might be a good idea to reconsider the term "hill fort" because what lies at the top of The Wrekin probably wasn't really a "hillfort" at all.

"I do not like to use the term ‘hillfort' as it implies that the site was defended and prone to conflict," he said.

"Instead, I prefer to use the term ‘hill enclosure’.

"Similar to a medieval castle, a moated manor or a stately home, the rampart earthworks and ditches would have been constructed to impress the power and prestige of the tribal group."

This observation, by itself, gives us some insight into what life was like for these ancient folk, as it suggests some sort of hierarchical social structure, and also a world where conflict was the exception and not the rule, pretty much as it is today.

Dr Nash added: "In terms of looking for archaeological evidence of conflict, there is very little [in the region] say the odd beheaded Roman slumped in a ditch in a Herefordshire hill enclosures site."

That's not to say that the Wrekin wasn't an effective defensive position. As the below images - taken using a drone camera this month - show, the enclosure would've given the locals a superb view across the region, maybe even better than the view we can enjoy today.

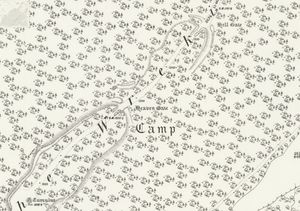

"During the final millennia BCE, the Wrekin was constructed to encompass the whole of the summit of the hill and at this time the summit and slopes were largely treeless," Dr Nash explained.

"The hill enclosure would have therefore had compass views across much of the eastern Shropshire landscape and would have been inter-visible with other hill enclosures, such as the mighty Old Oswestry hill enclosure, some 55 kilometres to the north west."

But if battle wasn't on these peoples' minds 24/7, what did they spend their time doing?

Well, the "large multivallate earthwork" would have encircled a community of individuals with various skills, who had day-to-day lives just as we do. Most people, in fact, would probably have lived outside of the enclosure itself.

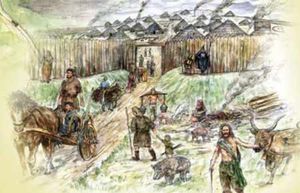

Dr Nash said: "The defensive earthwork would have enclosed an area of around eight hectares and would have been occupied or used by a large community of farmers and craft specialists, such as metal workers, carpenters, tanners and pottery makers.

"It is more than likely that the majority of the population using the sites would have lived in farmsteads that were dispersed across the immediate landscape.

"The Wrekin would have therefore acted as a centralised economic and social hub where weekly or seasonal markets and food distribution would have taken place," he continued.

"During this time livestock (cattle and sheep) were traded among the farming fraternity, along with the most prized possessions – horses."

Dr Nash presents The Wrekin as a social and economic centre, kind of like a town hall or Sunday market, as opposed to a residential zone. But that doesn't mean no one at all lived on top of the hill.

"Limited occupation within the confines of the enclosure would have occurred," he said.

"Those living within the earthen ramparts of the Wrekin may have been the elites, living in stone-lined roundhouses with conical thatched roofs.

"As part of their role, these people would have constructed and managed grain drying houses and pits which would have supported the population (similar to the role of the medieval tithe barn).

"The Wrekin would have also been a focus for Celtic [Iron Age] annual ritual and festival events, again similar to those we experience today in most modern religions (e.g. Christmas, Easter, Ede and Ramadan)."

We know, to an extent, from the archaeological evidence what sort of houses the Cornovii might have lived in and that the Wrekin was more of an "administrative centre" than defensive structure, which must be interesting to those readers who previously saw it as a fort.

What's also interesting, and perhaps somewhat ironic, is that southern British tribes were trading goods with their European neighbours at the time, and this may have caused the Cornovii around The Wrekin to start feeling uneasy as European culture began to integrate with theirs.

There was a contraction of the enclosed settlement on top of the hill in the 4th century BCE. No knows for certain why, but there are plenty of theories.

"Was this constriction due to population dynamics, forced by plague or political unrest?" Dr Nash asks. "Are we witnessing a change from enclosure to hill fort?

"Current thinking suggests that despite the significant contraction in size, the enclosure would have supported a large community.

"We know that during the latter part of the 4th century BCE and beyond, Celtic [southern] Britain is trading with Europe," he continued.

"Were the tribal communities of the Marches, and in particular, the people occupying the hill enclosures of Shropshire beginning to feel an uneasiness with European traders, in particular, those aligned with the military ambitions of Rome?"

It's an incredibly good question as several generations later, there's evidence the settlement on The Wrekin was "deliberately destroyed by an advancing Roman legionary force in AD48 or 50".

Dr Nash explained: "The Iron Age [Celtic] communities of the Marches and Wales would have probably known of their impending doom many years previously.

"The stress of Roman invasion and occupation was supported by the discovery of two Roman javelin spearheads dating from the mid-first century, one from the Wrekin and the other from the lower slopes of nearby Ercall Hill."

So, the Cornovii of The Wrekin were artisans, farmers and traders; a possibly religious people with a bit of warrior thrown in for good measure.

If The Wrekin did primarily become a defensive 'hillfort', during the latter centuries of antiquity, there's a good chance it was still no match for the military might of Rome.

*Dr George Nash has just been appointed as an Honorary Research Fellow within the Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology at Liverpool University. He's an archaeologist & specialist in Prehistoric and Contemporary art.