How fake spy Robert Hendy-Freegard isolated and humiliated students with his web of lies

He was an impecunious barman working at a pub popular with students. He left school with no qualifications, and had struggled to hold down a full-time job ever since.

But when Rob Freegard invited one young punter to stay behind for a chat at the end of his shift, it was the beginning of one of the biggest, most audacious, and cruellest cons in modern criminal history.

Freegard – or Robert Hendy-Freegard as he was later known – duped his victims out of more than £1 million over the decade that followed. But more than that, he scarred them for life, coercing them into years of virtual house arrest, isolating them from their friends and family, and subjecting them to humiliating tests to prove their loyalty. His crimes now form part of a three-part documentary series launched on Netflix today.

The Puppet Master: Hunting the Ultimate Conman tells how the penniless drifter conned people far better educated than himself with fanciful stories about his supposed work for the security services.

Sometime in 1992, Freegard took a job at The Swan at Newport, between Stafford and Telford. The pub was popular haunt with students from the nearby Harper Adams agricultural college, and the smooth-talking 21-year-old made quite an impression on many of the young punters. He might have been living out of a suitcase in a shabby room above the pub, but his confident, self-assured manner and endless patter about fast cars and expensive watches kept them mesmerised.

At Christmas 1992, Freegard started dating fourth-year student Maria Hendy, who introduced him to her friends John Atkinson and Sarah Smith.

It is possible that Freegard's grooming of the trio might actually have begun as nothing more than a sick prank. At closing time on January 29, 1993, Freegard beckoned Mr Atkinson over and invited him to stay behind after the pub closed.

At this time, Mr Atkinson was in a vulnerable state of mind. Three weeks earlier, his friend, an Irishman called Garry, had taken his own life by shooting himself in the head. Freegard took Mr Atkinson to a quiet corner of the pub, and told him he had inside information that Garry had not taken his own life, but had been murdered. Garry, he said, had inadvertently come across an IRA cell at college, whose members had been using fertilisers to make bombs. The terrorists decided Garry knew too much, Freegard told him, and decided to silence him for good.

The story struck a nerve. Mr Atkinson, a 22-year-old from a wealthy background, had led a sheltered life. And the day before an IRA car bomb had exploded outside Harrod's.

Freegard told the student to keep an eye on his friends. The following week Mr Atkinson reported back to him with a list of possibly suspicious activity from the Irish students.

While his tall tales may seem implausible today, it is important to remember that at the start of 1993, Shropshire and the wider West Midlands was on a state of high alert.

There had been two IRA attacks in Shropshire, first at Ternhill Barracks near Market Drayton in 1989, and then at Shrewsbury Castle just months before he came up with the story. Furthermore, former Harper Adams student Kevin O’Donnell, a gun-runner for the IRA, had been shot in the head in an ambush.

Gradually, over the coming months, Freegard took Mr Atkinson, Miss Hendy, and their friend Sarah Smith into his confidence, convincing them their lives were in danger and the only way they would survive would be to do exactly as he told them. He moved them into a series of squalid "safe houses", and isolated them from their friends and family.

He also put them through a serious of humiliating tests to prove their loyalty.

In one particularly malicious case, he took Mr Atkinson down to the cellar of The Swan. There, Freeguard blindfolded the young man, and dealt him a vicious beating. The student obediently endured the attack to prove his loyalty to Freegard, and show he was ‘hard enough’ for the work that lay ahead.

In another test of loyalty, Freegard also instructed Mr Atkinson to carry out a series of bizarre missions which quickly alienated the student from his friends. It was estimated he had conned Mr Atkinson and his wealthy family out of the best part of £400,000.

Wanting to bring Miss Smith closer into the circle, he encouraged Mr Atkinson to pursue a relationship with her. She then dropped out of her degree course at Freegard’s behest and handed over her entire inheritance of £180,000.

But Freegard's hold over Miss Hendy was even more extreme. The conman entered into an exploitative relationship with her, producing two daughters. It was at this time that Freegard added her name to his, changing it by deed poll to Hendy-Freegard.

But while Hendy-Freegard lived a jet-set lifestyle travelling the world, Maria was required to hand over every last penny to finance his ‘operations’.

Over time he bought himself seven BMWs, an Aston Martin Volante, Rolex watches and a wardrobe full of Savile Row suits.

But this was only the start of his deception. While he was supposedly away on missions to save the nation from terror, Freegard began expanding his web of deceit to draw other wealthy young people in.

Another victim, Elizabeth Richardson, slept on park benches and in airport terminals as she lived on £1 a week by eating bread and Mars bars. He coerced Kimberley Adams, a 37-year-old American child psychologist, to hide in a bathroom for a week.

After telling Hendy, Atkinson and Smith their cover was blown, Freegard instructed them to move with him to Sheffield where he took a job as a used car salesman.

He fed them stories that their lives would be in danger if they shared their movements with anyone else. They were instructed not to talk to their families as their phones would be tapped, and warned that bogus police officers would come looking to lure them into a trap.

In her book about the ordeal, Sarah Smith told how weeks into her relationship with Mr Atkinson, her new boyfriend announced he had liver cancer.

Freegard had persuaded Mr Atkinson to make the claim, and organise a “farewell tour” of Britain for the group during college holidays.

The two couples set off at Easter 1993 for their tour, travelling by rail from one end of the country to the other, staying in the cheapest guest houses they could find.

Days before they were due to return to college, Freegard took them to the beach in Bournemouth and told them they would not be returning.

“There’s a reason I’ve been placed at The Swan,” he told them. “We’ve identified an IRA cell at Harper and it’s my job to root it out. The college is thick with Provos, and John’s been helping me.

“We’re not just here because of John’s illness, but because we need to lie low for a while. Our cover has been blown. Mine and John’s.

“Unfortunately, by being associated with us there are contracts out on your lives as well. Going home won’t be allowed until some arrests have been made. We hope this will happen in the next few weeks.”

In her book, Miss Smith likened the bombshell to standing on a cliff edge.

“I could picture armed men in balaclavas positioned around my home, while Mum busied herself with the church calendar and Dad examined his cauliflower seedlings,” she wrote.

The two couples moved to Sheffield, where Mr Atkinson got a job in a pub, and his girlfriend went to work in a chip shop. Freegard, himself, meanwhile, became a car salesman, using his skills so entice a number of other well-heeled victims along the way.

One night, before they were sent to separate safe houses, Miss Smith recalled saying to her boyfriend, “Something is not quite right”. Mr Atkinson simply replied: “This is too insane to be a con.”

The plot began to unravel when Mr Atkinson confided in his sister that he was on the run from the IRA, sparking immediate suspicion.

Miss Smith's father Peter was also suspicious, having decided from the beginning that Freegad was not to be trusted. His suspicions were confirmed when he contacted police.

Solicitor Carolyn Couper, who met Freegard when she bought a car from him in 2001, also went to the police after £14,000 was stolen from her bank account, but there was not enough evidence to take any action.

By this time, Freegard had conned too many people and it was a matter of when, not if, he would be caught.

And as with so many conmen, his downfall came when he got too greedy. And in August 2002 he pulled one con too many.

When Freegard discovered American child psychologist Kim Adams was the stepdaughter of a $20 million lottery winner, he thought he had struck gold. After telling Miss Adams’ bosses that she had terminal cancer, he then told her mother that they needed $15,000 to send her to spy school.

What he didn't realise was that the real security services were now taking an interest in his supposed espionage activities.

Det Sgt Bob Brandon, who had for a while been investigating Freegard's activities for the Metropolitan Police, decided it was time to seek the advice of an old friend, Special Agent Jaclyn Zappacosta of the FBI.

So when Freegard contacted Miss Adams’ mother in the US, the FBI was already on to him, and Mrs Adams had agreed to have her phone tapped. She agreed to travel to London with $10,000 on condition she could see her daughter, and the police were waiting.

The king of conmen had finally been duped himself.

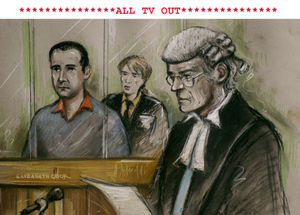

Hendy-Freegard was arrested in 2003, and on June 23, 2005, after an eight-month trial, Blackfriars Crown Court convicted Robert Hendy-Freegard for two counts of kidnapping, 10 of theft and eight of deception. On September 6 that year, he was sentenced to life in prison.

It later emerged that this was not Hendy-Freegard's first brush with the law. A year before meeting the Harper Adams students, the Nottinghamshire-born conman had been in a relationship with 26-year-old schoolteacher Alison Hopkins. But the relationship soured when he broke into her home, stole her credit card and raided her bank account. He was convicted on two counts of theft, and ordered to pay the money back. It was also alleged Freegard had paid two heavies to abduct Miss Hopkins, but the court did not pursue a more serious charge of attempted kidnap. Miss Hopkins moved to Newport to escape his clutches, but distraught at the rejection, Freeguard followed her to Shropshire.

DS Brandon described Hendy-Freegard as the most accomplished liar he had met in his entire career. Even agent Zappacosta, who had seen some pretty audacious stunts in her time, was left in disbelief by what Freegard had done.

DS Brandon said after the trial: “He ruthlessly deprived his victims of many years of their lives by making them believe their lives were in mortal danger.

“He lived a millionaire lifestyle while they lived in abject poverty.

“He was motivated by power; he was a sad, pathetic individual who achieved nothing from his life, but by pretending to be a spy he had power and control over people.”

But there would be a final twist.

In 2007 Hendy-Freegard successfully appealed to the House of Lords, arguing that his convictions for kidnapping should be quashed as he did not physically prevent them from leaving him.

In what was seen as an important test case for the definition of kidnapping, he managed to get the convictions quashed and the life sentence was revoked, on the basis that his victims were not forced to live with him.

He served a nine-year sentence for the other offences.