The raw sounds of nature in autumn: Artist Ben Waddams says the activity of wildlife in October is exciting to behold

This month is surely one of the most exciting in the wildlife calendar. For myself as a wildlife artist, the palette is richer than at any other time of the year and the species that make their presence known are amongst the most impressive, writes Ben Waddams

The largest land mammals in the UK are in the midst of their annual rut during October. This is the peak of the Red Deer mating season, a dramatic and often noisy period that brings a raw, primal energy to the countryside.

We have a very few here in Shropshire with only a spattering along the Welsh border. Nearby Cannock Chase is, however, an excellent place to experience them.

Instead we have a much larger population of Fallow Deer, especially in the south of the county and the Mortimer Forest near Ludlow.

Either way, the first and second largest land mammals are similar in their habits this month.

Stags emerge from the shadows, their antlers polished from rubbing against trees and shrubs, and their muscles primed from weeks of preparation. They engage in vocal displays; deep, guttural roars that echo through the hills and woodlands, as a way to assert dominance and attract females. These roars are not just about bravado; they serve as crucial tools in avoiding unnecessary physical combat, warning rival males of their strength.

When it comes to physical battles, while rarely fatal, they are intense and exhausting, with the stronger, more experienced stags typically gaining access to groups of hinds. The rut is a time of high tension and activity. Patience and a respectful distance are essential; witnessing a rutting stag in full display is one of the most stirring sights in British wildlife.

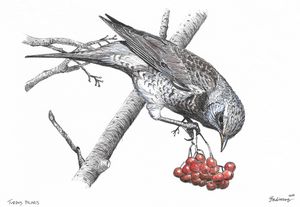

A less dramatic yet equally autumn-orientated sight in our local fields and hedgerows is the ripening of sloe berries. With an attractive bluish-purple sheen, they are unbearably tart to our taste straight off the bush. Yet heavily sweetened sloes go famously well with gin, and are excellent too in whisky, port and chocolate. Birds normally leave sloes untouched, much preferring hawthorn, holly and mountain ash berries but there are three species that will eat them; the mistle thrush, fieldfare and hawfinch.

The latter of these is a real marvel of our countryside and the good news is that their numbers are about to be bolstered by winter migrants from the continent. The Hawfinch is the largest finch in the UK, weighing more than twice as much as a chaffinch. In terms of viewing tips, the success I’ve had has been down on the Welsh border, around Powis Castle for example. However, despite their size, they are very hard to spot due to their elusive behaviour, singing quietly from high in the canopy.

A bird that may be easier to spot is the dipper. A small, plump bird with a white bib and a distinctive habit of bobbing or ‘dipping’ up and down on river stones it is unique among British songbirds in that it can walk underwater, using its wings to help navigate the current as it forages for aquatic insects, larvae, and small crustaceans.

Uplands tend to empty of birds after the breeding season, before harsher weather sets in but the dipper often simply moves downstream, making them easier to observe and enjoy. Gone are the days when one would need to hike up a mountain stream; for the next few months they can be seen beside wider rivers and around the shores of lakes and reservoirs, looking strangely out of place.

And finally on the easel this month is the badger. They are now focused on fattening up for winter.

While they don’t hibernate in the strict sense, they do spend much of the colder months in a state of torpor, reducing their activity and remaining underground for days or even weeks at a time.

To prepare for this, badgers intensify their foraging in the early autumn. Earthworms remain a key part of their diet, but they also feast on windfall fruit, nuts, and any remaining cereal crops, especially maize.

Woodland edges and hedgerows become bustling foraging grounds, often with whole family groups, known as clans, emerging together in the twilight. Healthy badgers should weigh a third to a half more than in summer. But milder winters mean they are less dependent on fattening up than they once were, as most nights they can still leave the sett and find food. So whether dramatic or subtly interesting, this month is always rewarding for the naturalist in Shropshire’s wilds.

Ben Waddams is a wildlife artist. See his new work in Callaghan’s Gallery, Shrewsbury