1945: Churchill gets boot by wind of change

As we prepare to go to the polls, Toby Neal starts a weekly series on historic elections.

It was a landslide election result which underlined a seismic change in Britain. The 1945 general election saw Winston Churchill, the great war leader, unceremoniously washed away by a red tide of Labour.

After six years of the hardship of war, voters turned their backs on the old guard and the old ways. They wanted to build a different and modern path for Britain in the post-war era.

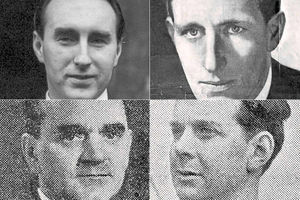

The wind of change in 1945 introduced a quartet of brand new faces as MPs to Shropshire's four Parliamentary seats, three of whom were men in uniform who had fought during the war.

Despite Labour's stupendous victory at national level, Shropshire remained true blue, with only one seat, The Wrekin, falling to a Labour candidate.

He was Ivor Thomas, who won the seat from sitting MP Arthur Colegate with a sizeable majority for Labour.

Thomas had a trade union background. He had been adopted as candidate by the local Labour Party in February 1938, but he hailed originally from South Wales, his home town being Briton Ferry.

Unlike the rest of the country, voters in The Wrekin had had a wartime Parliamentary election, which came in tragic circumstances. Colonel James Baldwin-Webb, the Tory MP since 1931, was killed in 1940 when the liner City of Benares was torpedoed by a U-boat. A by-election in September 1941 saw Colegate, a National Conservative candidate, elected.

Elected at Shrewsbury was a local man who was destined to be Shrewsbury's MP for many years, finally stepping down in 1983. He was 29-year-old Commander John Langford-Holt. His parents lived at Port Hill, Shrewsbury.

Commissioned into the Royal Navy, he flew in the Fleet Air Arm and according to newspaper accounts when his candidature was announced he took part in most of the actions of the Home Fleet, including attacks on the feared German battleships Bismarck and Tirpitz. He was on an escort ship on nine Russian convoys.

Ludlow's successful candidate was 36-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Uvedale Corbett, who had the nickname "Streak". The story goes that this was acquired when his fellow officers described him as a "long streak of misery" when a horse on which he had had a flutter was pipped at the post.

Corbett's home was at Stableford, near Bridgnorth, although he had not spent much time there since joining the Army. He served in the Royal Artillery and was a war hero, having been awarded a Distinguished Service Order in August 1944 in Normandy during the capture and defence of the Orne bridgehead.

Disregarding enemy shelling, he had climbed on top of his vehicle in the open to direct artillery fire during repeated attacks by an SS Panzer Division.

Winner at Oswestry was Colonel Oliver Brian Sanderson Poole, a member of Monty's Montgomery's headquarters staff. Aged 34, he had a distinguished record of service in North Africa and Europe. He was a member of Lloyds, the insurance brokers.

Huge numbers of those entitled to vote were serving in the armed forces across the globe. The election was called within weeks of the end of the war in Europe, but many were still fighting the undefeated Japanese in Far East.

Because of this voting took place on July 5 and the result was announced on July 26, to enable votes from those serving overseas to be processed.

The war had thrown people together from different backgrounds, and those from more impoverished circumstances came to appreciate just how disadvantaged they were. Living conditions for many were hard, slums were everywhere, and basic services which are taken for granted nowadays, like indoor toilets, were often absent. Before the war, communities were ravaged by high unemployment.

There was a radical spirit and an appetite for change, which was particularly marked among the rank and file in the armed services. Having done their bit in war, they were not looking to go back to the way things had been. For some in uniform "Uncle Joe" Stalin, a wartime ally, was quite literally their poster boy.

Churchill had led a national all-party Government since the dark days of 1940 but it came apart after the Allied victory in Europe as the consensus broke. The 1945 general election was the first in Britain for 10 years.

The result was an overwhelming Labour victory. After his years of war leadership it was like a kick in the teeth for Churchill. Voters had decided that the qualities Britain needed in peace were not the same as they needed in war.

His wife Clementine told him it might be a blessing in disguise, to which he famously replied: "If it is a blessing, it is certainly very well disguised."

He had not seen it coming – nor had hardly anybody else. Labour gained 239 seats and had a 48 per cent share of the vote. For the Conservatives, it was a heavy blow. They were down to only 197 seats. For the Liberals, it was a complete disaster. In the space of only a generation, they were destroyed as a Parliamentary force, ending up with only 12 seats and being turned from a party of government to a fringe party.

In the new Parliament, Labour had 393 seats and an overall majority of 159 over all other parties.

In as Prime Minister came Clement Attlee with a decisive mandate to change Britain and introduce the National Heath Service, the welfare state, and the nationalisation of things like the railways, the mines, and the iron and steel industry. There were too far reaching educational reforms. Among that 1945 influx of Labour MPs were many who were to become the Labour leaders and Cabinet ministers of the future.

And in Shropshire? There was one, solitary, Labour gain, in The Wrekin, where Ivor Thomas took the seat from the Tories. It was the first time that Labour had won the seat since Edith Picton-Turbervill had won it in 1929 to become Shropshire's first, and so far only, woman MP.

In the other three Shropshire constituencies, the Tories held on comfortably.

In Shrewsbury there was a small crowd by the riverside steps of Shrewsbury Technical College to hear the result declared by the High Sheriff and returning officer, Lieutenant Colonel GP Pollitt.

It was a sentiment echoed by Colonel Uvedale Corbett at the declaration in Ludlow.

When Shropshire boffin Harold married Attlees daughter:

As Clement Attlee took office, little did Salopians know that it would not be long before romance would forge a link between the Prime Minister and Shropshire.

Harold Shipton was a bespectacled lad from Shropshire, the quintessential image of a boffin, and a brilliant scientist.

And he was to create a minor sensation when he married the Prime Minister's daughter.

It was at a party in Bristol, where Harold had moved from Shrewsbury in the spring of 1946 to work at the Burden Neurological Institute, that he had first met Janet, who was working at the Bristol Mental Hospital (as it was called then).

Romance blossomed and she agreed to marry him.

Now came the tricky bit where Harold, who was only earning about £5 a week, had to meet the future father-in-law.

He had already got to know her family a little after being invited to stay at Chequers, the country retreat of the Prime Minister.

"Until I got to know them better, they seemed to me to be inclined to be snooty," recalled Harold in later life.

After receiving the blessing of the Prime Minister to the marriage – they got on well – it was Janet's turn to meet Harold's family in Coton Mount, Shrewsbury. They lived in a 1920s council house with no lighting upstairs.

The wedding of Harold and the eldest daughter of the Prime Minister in November 1947 was a society event, and the newsreel cameras were there. The reception was held at Chequers.

Professor Harold Shipton, who was known as "Shippy" to his friends, died in 2007, at the age of 86.