Shropshire's near-forgotten giant of charity

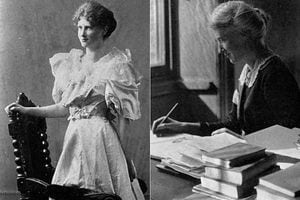

She was Shropshire's most influential figure of the 20th century.

She was a woman whose drive and fundraising commitment pioneered techniques which are today basic concepts of international aid agencies.

Eglantyne Jebb was the Bob Geldof of her own time and, like Sir Bob, was prepared to make a stir to get things done.

She realised that it was important to get her charity's message across and gain publicity for its appeals for aid. She took out page length newspaper advertisements – seen by some as "vulgar commercials" – and battled on behalf of starving infants against an initial tide of apathy in Britain about conditions in former enemy countries.

Her work saved the lives of untold numbers of children across the world and improved the lives of many more. Her legacy is that it continues to this day, many years after her death.

The accolade of Most Influential Salopian of the 20th Century, in which she faced stiff competition from other worthy claimants, was bestowed in 2005 by the Shropshire Society In London, which fosters the links between the county and the capital.

He was the Duke of Wellington's "most trusted general" at the Battle of Waterloo.

And now a project has begun to celebrate the life of Lord Rowland Hill – who remains a familiar sight nearly two centuries after his death thanks to the column that was erected in his memory in Shrewsbury.

Lord Rowland Hill, born near Hawkstone in 1772, was the second-in-command at the Battle of Waterloo, which took place on Sunday, June 18, 1815, about 10 miles south of Brussels.

It saw the French, under the command of Napoleon Bonaparte, do battle with the Allied armies commanded by the Duke of Wellington and Prussia's General Blücher.

The French defeat brought to an end 23 years of warfare that began with the French Revolutionary Wars of 1792 and ended Napoleon's bid to make France a European empire.

Two hundred years later, Shropshire Council and a number of venues will be hosting events to mark the county's link to the victory.

The project organisers say they hope it will "put Shropshire on the map" and they are also appealing for any new information or artefacts relating to Lord Hill and the battle.

An online visitor trail and guide to Shropshire's links with Lord Hill is planned, along with a diary of events and activities which will be released later the month.

Venues will include Shropshire's Regimental Museum at Shrewsbury Castle, open days at the Lord Hill Column, Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery, St Chad's Church, and Weston Park.

Nigel Semmens, a committee member for the Friends of Lord Hill Column, said the anniversary provides an exciting opportunity for Shropshire to capitalise on its links to the battle.

He said: "It is very, very exciting in that this is the anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo and Shropshire is particularly fortunate to be able to boast that it houses this spectacular Grade II* listed monument. The view from the top is stunning and we obviously hope as many people as possible will be able to visit the column.

"He was Wellington's most trusted general. Wellington said this on many, many occasions but he was one of the top good guys. He really cared for his troops and earned the nickname 'Daddy Hill' as a result."

Eglantyne, from Ellesmere, was chosen from 24 nominations.

As it happened, a poll showed that Eglantyne was not the most popular choice among Shropshire Star readers, which says something else about her – she is, relatively speaking, one of Shropshire's forgotten heroines.

No less a person than the Princess Royal, who has been President of Save the Children since 1970, has called for her profile to be raised.

Eglantyne was the co-founder of that charity, championing the cause of the forgotten child victims of World War One across Europe, and inspired ordinary people to help them.

"The world is not ungenerous, but unimaginative and very busy," she wrote.

A "children's charter" she drafted in 1923 was a forerunner of the 1991 United Nations convention on the rights of children. It was underpinned by the belief that children should be helped "above all consideration of race, nationality or creed''. It remains the cornerstone of the Save the Children charity.

In 2013, 15.4 million children were helped directly through Save the Children's work on the ground, according to the charity's website, and 9.7 million helped through health and nutrition programmes. In just one year.

One of six children herself, Eglantyne was from a well-known and well-off Shropshire family. It was a privileged upbringing. But Eglantyne was not prepared to accept the narrow horizons which were available to women in her time, and she grew into a young woman with a determination to do some good in the world.

She saw at first hand the plight of children in the East End of London and, against the wishes of her mother, trained to become a teacher.

She turned out not to be a very good one, being unable to cope with unruly children.

It was the aftermath of an early Balkans conflict which gave her a first taste of how a large-scale relief effort would need to be organised.

She went to Macedonia at the request of the Macedonian Relief Fund in 1913 to assess the needs of the refugees.

Soon the whole of Europe was engulfed in war. The Allied blockade of European ports caused great hardship.

As the war drew to a close Eglantyne risked being called a traitor by campaigning on behalf of the innocent victims. Her simple humanitarian message struck a chord. A Fight The Famine Council was formed, primarily to relieve the suffering of children, and in 1919 Eglantyne and her sister, Dorothy Buxton, founded the Save the Children Fund.

Some members of the public arrived to the public meeting to launch the appeal armed with rotten apples which they planned to throw at the head of the traitor who was speaking up for "enemy children". Instead, as she spoke with passion, they listened.

While she is of course rightly remembered for her good works, she was also an intrinsically fascinating character.

There is a great irony in that she does not appear to have been fond of children herself. She once called them "little wretches".

She grew into an attractive – some say beautiful – young woman with a social conscience and a taste for solitude.

Although there was no shortage of admirers, she never married.

Later in life she went rock climbing, skiing and tobogganing.

Dogged by ill-health, Eglantyne's hair went white prematurely, and she died in Geneva in 1928 aged 52.