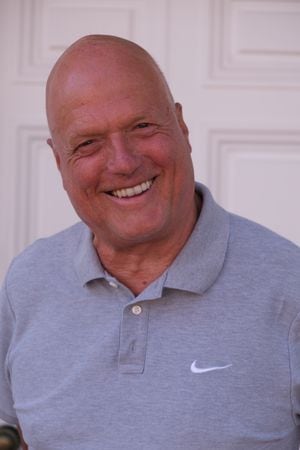

Meet the businessman who transformed foster care and made millions in the process

Businessman Jim Cockburn defied his critics to transform foster care and make millions in the process. But he faced an uphill battle from the start.

The fun starts when the interview ends. Jim Cockburn has sat through a two-hour inquisition.

There’s been laughter aplenty. There’s also been more self-analysis in an afternoon than this exceptionally successful businessman is used to in a year. From the airy confines of his light, minimalist, Edwardian office, the man who single-handedly transformed the fostering system not just in the UK but around the world has reflected on his improbably successfully career. It began in the West Midlands and saw him make tens of millions of pounds.

Having opened newsagents, the worst thing he ever did, he went on to buy supreme race horses in a bid to win the Derby. Having started with nothing he built a business and bought out his fellow directors for £25 million. He’s lost large sums of money on failed ventures, the inevitable misdirected punt on Chinese imports among them, while generating considerable wealth that has bought him a valuable collection of contemporary art and two stunning homes.

When we get to the end of the interview, Jim’s shoulders relax. “Have you seen the Tipton Monkey?” he asks. I shake my head in apology. I’ve not. “Have you? He’s brilliant.” We’ve spent two hours talking about protecting children from abuse, dozens of business ventures and art. But at the end there’s a swell of relief as he gets back to the banter he loves.

“It’s hilarious,” he says, describing a YouTube video of a Black Country man whose face is converted through the magic of computer software to that of a monkey. “He says he’s been in Dudley Zoo for years but he goes home every night, to Tipton. He loves living in Tipton. He doesn’t stay in the zoo overnight, he just turns up each day to make a few quid from the punters then he goes home.”

Chances are, you won’t have heard of Jim Cockburn before today. Yet he has played a huge part in the lives of countless people across the West Midlands, Staffordshire and Shropshire. His businesses have helped provide foster care for 45,000 children around the world, including many in this region. He is a humanist and carer, an entrepreneur and philanthropist, a poet and an art collector, a father and a three-times-married husband.

It’s only at the end of the interview that his motivations become clearer, that the Real Jim Cockburn looms into view. During the course of an afternoon he’s spoken at length about his father, a carouser who had a tune in his heart and beer in his belly, who won the Military Cross but couldn’t communicate effectively with his son and who also didn’t really make the grade as a businessman, always running out of money when it should have stuck like glue. Jim’s father was a rebel, too, a man who didn’t give two hoots for convention, authority or the rules.

“He was very posh, but he had PTSD from the war.”

He opened pubs and Jim helped clean the glasses and serve from the age of 12, giving the kid a redoubtable work ethic.

But it’s when Jim speaks about his mother that the arc of his life starts to make more sense, that the reasons for his drive become evident.

To steal from the lyrics to the Prince song, When Doves Cry: “Maybe you’re just like my mother, She’s never satisfied (she’s never satisfied).”

Jim says: “My mother loved my dad but she spent all her time trying to control him and trying to turn him into something he wasn’t. He was flagrant with cash, so she was always worried about money. He was always in the pub, there was always a row, he’d go to sleep, there’d be a row. She adored him, but it wasn’t that healthy a relationship.

“As a mother, she split me and my sister, we don’t talk anymore. She divided and ruled. She was highly critical. She lived to 100. I went to see her one day and she said ‘Why have you got those awful shoes on?’ She said that 13 times. She was 100 and she was still treating me like a kid.”

Consequently, there’s been a search for validation, a desire to prove himself. It’s fuelled Jim’s life. He laughs, a little despairingly, accepting the point. “Nothing was ever good enough. I still feel like a failure on a day-to-day basis. I’m still trying to prove myself. I always wanted to be good at something. I always wanted to have a demonstrable skill, like being a piano player at the Royal Albert Hall or becoming a runner who was genuinely good.”

Today he lives in two colossal houses, one in Edgbaston, the other in north Worcester, both of which are beautiful. He oversees labyrinthine business interests that helped to earn him a fortune, the key outlet being the Martin James Network.

In many ways, he created the fostering industry that the world knows today. Before he disrupted the previous rules, foster carers would get a pittance for providing care. He created an agency that aimed to take kids out of institutions, ensured carers were paid a reasonable allowance and most importantly created feelings of belonging and inclusion among frequently-abused kids whose life chances would have otherwise been curtailed. His fostering company dominated the UK, though he sold it to pay off his second, expensive divorce, to his former wife, Jan, who had helped him to create it. Today, however, he still operates parts of it, particularly those that provide fostering services in Australasia.

He heads the Martin James Network, a conglomerate for mould breakers and change makers who refuse to swim with the tide.

He started off as a social worker in Bristol, Sheffield and London, before moving to Dudley, where he stayed for two or three years. He moved to Sandwell as a social services middle manager during the mid-1980s. He worked in Smethwick, Oldbury and Cape Hill, concrete jungles that were areas of deprivation, and led scores of care proceedings where children were removed from the family homes.

“We could have made a case to take any number of kids away, I felt burned out.” He didn’t fit into the local authority ethos, rebels never do, so he moved to a night duty team before getting onto a course at UAE, in East Anglia, so that he could improve his knowledge and skills. He was told by a lecturer that he would never succeed with local authorities. “I was told my career would always be a disaster, that I’d always be in trouble.” He was too outspoken, too independent.

Jim led a union strike for more staff before he getting into trouble over the smallest things; like ordering office furniture more comfortable than that his directors had. He didn’t fit in and knew he never would.

He tried to change the direction of his career, applying to work in fostering. Ironically, for a man who went on to oversee 45,000 foster placements, he was turned down and told he’d make the process too elitist, so he switched to a night duty team in Wolverhampton. Then he stuck two fingers up at those who’d rejected him by creating the industry’s most successful business of all time. How do ya like those apples?

He may not have run a four-minute mile or played piano at the Royal Albert Hall, but it was equally accomplished, his raison d’etre, and served to revolutionise foster caring. “There was a girl there who started it all off. She was six or seven. She’d been multiply abused, sexually abused, given away to her aunty and uncle twice and they’d abused her too. She was wild. I took her into care and she was only a young kid and she ended up in this institution with teenagers, which was just wrong. So I spoke to a foster carer who I knew and asked her to look after her, rather than put her in an institution.”

By accident, Jim came across adverts for independent foster caring. There were no regulations and no rules. There were no barriers to entry. He learned fast and decided to give it a go himself, setting up an agency.

“We placed a lot of kids from Staffordshire. We rented a house and we had kids all over the place. Eleven of the first 19 kids were from Staffordshire.”

He started opening schools and at one point had three. He bought an old bail hostel and did that up as a school and offices. “We had 2,000 kids on the books, in the end.” The business boomed. Jim’s company had become a world leader. “We had a £50 million business in Australia. We were finding kids in hotels and motels all around the world.” Jim took them out of those hotels and motels, which were inappropriate settings, and got them resettled in homes with families. They blossomed. On such decisions can lives flourish.

“I believe really strongly that kids are better with families, not in institutions.”

He added: “We’ve saved kids’ lives, without a doubt.”