Brexit one year on: What can we expect in the next 12 months?

A year ago Britain went to the polls in the vote which sent shockwaves around the world. By a margin of 52 per cent to 48, the people of the UK voted to leave the European Union in a result which very few people expected.

It resulted in the immediate resignation of Prime Minister David Cameron, a mutiny in the Labour Party, not to mention last month’s snap General Election which cost the present PM, Theresa May, her majority. And then there was the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States, which he described as “Brexit plus plus plus”.

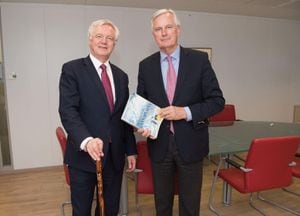

This week, Brexit Secretary David Davis sat down with the EU’s chief negotiator Michael Barnier for the start of negotiations which will see Britain leave the bloc within the next two years.

So, after a tumultuous 12 months, what can we expect for the year ahead?

“More surprises,” is the response of Professor Andy Westwood, who is director of Wolverhampton University’s observatory, and a former special adviser to the Government.

“It is the year in which everything has happened, we have had leaders leaving left, right and centre, Labour in turmoil, but then going on to put in a good performance in the General Election, and we are still in the phoney war over Brexit itself,” he says.

When Prime Minister Theresa May gave her Lancaster House address in January, it appeared to clear up at least some of the confusion about the direction Britain was heading in. She said Britain had clearly voted to take back control of powers regarding immigration, and that remaining as a full member of the Single European Market – which would have prevented that – was out of the question. She also ruled out remaining in the customs union, which would prevent Britain from unilaterally negotiating trade deals with other countries. It looked like we were set for what some of the pundits termed a “hard Brexit.”

However, these carefully laid plans were thrown into disarray following Mrs May’s disastrous decision to seek a fresh mandate by calling a snap election.

The Fixed Term Parliament Act had meant that there was not due to be a general election until May 2020, and Mrs May had repeatedly said she had no intention of calling one. However emboldened by opinion polls giving her a double-digit lead, she decided to go to the country just two years into the five-year parliament.

When she called for the election in April, she said she needed a larger majority to strengthen her authority in the Brexit negotiations.

“Our opponents believe because the Government’s majority is so small that our resolve will weaken and that they can force us to change,” she said.

“They underestimate our determination to get the job done and I am not prepared to let them endanger the security of millions of working people across the country, because what they are doing jeopardises the work we must do to prepare for Brexit at home and it weakens the Government’s negotiating position in Europe.”

However, instead of returning the landslide victory that Mrs May had been expecting, the Conservatives instead lost their majority in the Commons as Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party came within less than three per cent of the Tory vote.

Mr Westwood says that, just as Mrs May hoped a large majority would strengthen her hand with negotiations in Europe, the fact that she is now dependent on the Democratic Unionist Party to prop up her government can only have weakened it.

“I can’t imagine it can have done anything other than that,” he says.

“All the other leaders in Europe will have read about how she is struggling to form a government. The European media are well aware that she is weakened.

“I think, for all the posturing about ‘no deal is better than a bad deal’, it will be harder to walk away full stop, and follow that through.”

Not everyone shares that view. Arch-eurosceptics such as Stone MP Sir Bill Cash have argued that the General Election result has strengthened the mandate for Brexit, given that Labour went into the campaign with a remarkably similar policy on the matter. He says the fact that 86 per cent of the population voted for either the Conservatives, Labour or Ukip only underlines the fact that most people in Britain now want to leave the EU.

Mr Westwood is not convinced.

He says it would be naive to think that Labour’s commitment to Brexit is anything like as certain as that of eurosceptics such as Sir Bill. He says Labour is a party which is still very divided on the subject, and is very difficult to know how a future Labour government would tackle the issue.

“I think the only one who thinks the Labour position on Brexit is clear, unambiguous and settled is Corbyn,” says Mr Westwood.

“It made sense for them to go into this election with a policy not much different from the Conservatives, because their traditional voters overwhelmingly voted to leave, particularly in the West Midlands constituencies. But whether Labour will stick to that position remains to be seen.”

And while Labour’s better-than-expected performance in the election would appear to have secured his position within the party for the time being, he says it would be foolish to rule out one of the more centrist – and pro-EU – MPs staking a claim for the leadership in future.

“I think not even Jeremy Corbyn knows whether the closer-than-expected election result was because of him, or despite him,” he says. Students of recent political history will also remember that it was a revival in the opinion polls which persuaded the Conservatives to ditch Iain Duncan Smith as leader. It was only when they thought victory could be in sight that they decided their unpopular leader could be holding them back. Mr Westwood says it would be foolish to rule out Labour MPs coming to a similar conclusion, although of course Mr Corbyn has already demonstrated that his grass-roots support is enough to see off a challenge from within the parliamentary Labour Party.

Assuming that, as appears likely, that the Conservatives remain in office for the foreseeable future, Mr Westwood believes it is inevitable that the Government will have to soften its stance in negotiations with the other 27 EU countries.

He says we have already seen how the result has strengthened the hand of the pro-EU Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond, who had been widely tipped for the sack had Mrs May secured an increased majority.

Mr Westwood says we can expect to see greater emphasis on economic objectives, and the needs of business, as Britain enters the negotiations. “I think now business will try to do things, and this is where Philip Hammond becomes quite significant,” he says. “I think there will be far more talk about jobs and business, and far less emphasis on things like immigration.”

Mr Westwood says it is hard to tell whether the negotiations can be completed in the required time frame, or whether where will be some interim deal while the finer points are ironed out.

He says many of the delays in reaching a deal will be less about disagreements about policy, and more to do with the technical complexities that surround EU legislation.

“The level of technical detail they will have to go into is vast,” he says. “The most likely scenario, I think, is that the negotiations will be extended beyond the two years.”

For all the sound and fury that will dominate the headlines over the next couple of years, though, Mr Westwood believes the reality behind the scenes will probably be much more conciliatory. “I think the level of detail and complexities behind issues about technicalities do not lend themselves to media coverage,” he says.

“The media will want to simplify the narrative, and will portray it as being all about shouting and rows, whereas in reality it will be a lot more cordial. I think the officials will be trying to make as many friends as possible.”

Opinions still divided at cafe

The referendum split the public down the middle, with 52 per cent voting to leave and 48 per cent voting to remain. And, if the opinions of people at the Forge Urban Revival cafe in Wellington is anything to go by opinions are still very divided.

Assistant manager Stephen Handley says he chose not to vote in the referendum.

"I didn't vote because in the referendum because nobody could tell me what would happen, the Government couldn't say what would happen," says Stephen, who is 60.

Dropping in for lunch is Gemma Lattauschke, a 36-year-old dentist from Hadley, Telford.

"I'm disappointed we are leaving, because I would prefer to see the different countries staying together," she says.

Sipping a mug of coffee is Nigel Ruff. The 54-year-old factory worker from Wellington is delighted Britain voted to leave the EU, and is confident that the Government will secure a good deal.

"I'm glad we're leaving, it's a waste of money, it costs us £350 million a day," he says.

He says it is particularly important that Britain takes control of fishing in its waters, saying that EU quotas force British fishermen to throw dead fish back into the water.

"I think Theresa May is very good, I think she will get us a good deal."

He says he has no interest in a so-called "soft Brexit," which would see Britain remain in the European Single Market and mean we would still have to accept freedom of movement.

"We should go back to being an island," he says.

"If they want to trade with us, we should do a deal, but if they don't we should look at other countries to trade with.

"It shouldn't take two years to do a deal, we should be able to do it in six months."

Ken Purchase, who keeps a bed-and-breakfast in Allscott, Telford, also believes that Britain needs to get on with the process of leaving.

"I think the 48 per cent that voted to remain should respect the views of the other people that voted to leave," says the 64-year-old.

"I think Theresa May, and all the other MPs, should stop squabbling among themselves and come together to focus on getting a better deal for Brexit.

"I think we should have some kind of arrangement by which we can trade with Europe, and I think Europe wants to trade with the UK. Brexit, while having a trade deal could, I think be a very good thing for Britain."

He does concede, though, that the indecisive General Election could weaken Britain's hand in negotiations, although he thinks the difference will be small. He accuses Jeremy Corbyn of getting votes by making promises he would never be able to keep.

Sandie Dent, a 52-year-old project manager with a charity in Wellington, says she was in tears when she heard Britain had voted to leave the EU.

She says the past 12 months have been a "total shambles", and says the signs are not looking good for the future.

"I think its probably been the worst 12 months that I can remember in a long time, politically and socially."

Sandie says she is sad about the way the referendum has polarised society, with people taking increasingly entrenched positions on either side of the divide.

She believes many people voted to leave the EU because they felt frustrated their views were not being listened to.

"Many people didn't know what Brexit would mean, people didn't vote on what they thought they were voting for."