Half a century of colour TV

For a defining moment in broadcasting history, it was a decidedly low-key affair. It would change the way we watched television forever, but this newspaper devoted precisely two words to what made this televised tennis match unique: "In colour".

It is 50 years today since the BBC made its first colour broadcast, beating the German broadcaster by two weeks. But while it was an important moment in TV history, it is perhaps understandable that there was little newspaper coverage at the time, since very few people would have been able to watch it.

Back in 1967, there were thought to be fewer than 5,000 colour TV sets in the UK, accounting for about one in every 10,000 people. And given that a Ferguson 3700 Colourstar would set you back £362 – just over £6,000 at today's prices – it was something that was very much the preserve of the well heeled. On top of that, there was a £5 a year "colour supplement" which doubled the cost of the licence fee, so joining the TV revolution was something of a commitment.

John Logie Baird, the Scottish engineer generally considered to be the inventor of the television, had demonstrated that it was possible to broadcast in colour as long ago as 1938, when he sent a mechanically scanned image from his Crystal Palace studios to a projection screen at London's Dominion Theatre. His system made use of red, blue and green filters, which used radio waves to control the colour of the transmitted onto the screen.

However, the outbreak of the Second World War led to the BBC suspending its television service, and the research was halted, and Baird died in 1946. There had been experiments with colour broadcasting in the United States during the 1950s, but the vast cost meant it failed to catch on.

When the BBC launched its second channel in 1964, it was decided at the outset that the new station would focus on innovation and the use of new technology. From the start it would only broadcast on the 625-line format, which gave a sharper, clearer format, but meant that people with the older 405-line sets would not be able to receive the new channel.

Within two years of its launch, Postmaster General Tony Benn told the House of Commons that BBC 2 would become the first channel in Europe to broadcast in colour. The new service was estimated to cost the BBC between £1 million and £2 million a year, and would initially screen four hours of colour television each week, rising to 10 hours within a year.

BBC2 controller David Attenborough said the four hours of programming would be based on what the BBC could produce from its own studios, and said that in addition to this there would be imported colour programmes. He said the popular Western series The Virginian and The Danny Kaye Show, a variety programme from the US, were both available in colour, which led to concerns in some quarters that the move would herald an increase in repeats.

Attenborough assured viewers: "We have to remember that 95 per cent of people initially will not be seeing these programmes in colour, they'll be seeing them in black and white.

"The shows that BBC2 will be scheduling will be exciting new shows in black and white. They'll be that much more exciting and newer in colour."

Besides, by the time of the launch, some British television programmes were already being made in colour with a view to export. Hit spy series The Avengers was filmed in colour from 1966 onwards for the American market, although it was not until the series was repeated years later that British viewers would get the chance to see John Steed and his glamorous female sidekicks in all their colourful glory. Reflecting the programme's main market, the US spelling "in color" was used in The Avengers' opening titles.

The BBC, along with the other broadcasters in Europe, all agreed to use a common system to make it easier to share programmes. Eventually they chose the Phase Alternation Line, or Pal, over the American National Television System Committee (NTSC) system. Pal produced 50 frames per second, making it slightly slower than the American system, but offered a higher picture resolution. The European system was generally considered to be more advanced than NTSC, which cynics described as "Never Twice the Same Colour", whereas Pal quickly became nicknamed "Perfect At Last".

Initial response to the early colour broadcasts were positive, although the high cost meant that people were slow to take it up. Those that did take the plunge spoke of a greater feeling of realism when watching in colour, and it enabled and the broadcasts aim to exploit this interest by seeking more programmes that would benefit in colour, such as the snooker programme Pot Black, and children’s puppet series Thunderbirds. While millions had watched England's World Cup triumph over Germany in 1966, there was little doubt that the spectacle would have been much easier to follow had it been in colour.

Due to the lack of colour production facilities, the majority of early colour programming consisted of outside broadcasts and movies until the conversion of Television Centre studios 6 and 8, but by the end of 1967 BBC2 colour broadcasting had extended into the South West and South Wales, southeast and eastern England, and by early December the channel was broadcasting more than three quarters of its schedule in colour. Sport would continue to be an important part of the BBC’s early colour output, with the new one-day Sunday League cricket matches being shown in colour, along with a number of test matches.

Shropshire gardening expert Percy Thrower was another pioneer, his Gardeners' World being the first weekly programme to be made by BBC Midlands.

By 1969, the number of colour sets had risen to between 130,000 and 160,000, and this was the year that colour broadcasting would truly come of age. In May, 1969 the Government announced that ITV and BBC1 would also begin colour broadcasting from November 15, with Birds Eye peas becoming the subject of the first colour TV advert. By this time, many viewers had seen colour footage of the Apollo 11 spacecraft heading for the moon the previous July. TV had now entered the space age.

The Star's TV critic Bill Smith, said the introduction of colour across the channels was a much-needed boost after years of mediocre programmes.

"Not since the lusty arrival of commercial TV, soon to disappoint with a surfeit of sub-standard programmes, has this instrument of home entertainment so desperately needed a tonic," he wrote. One hates to think what he would have made of Love Island.

"Colour all round, long awaited and bitterly fought for, is a morale booster for everyone concerned with television.

"But it will not, in some magical way, make an unfunny comedian funny. Neither will it improve the dramatic quality of a poor play."

This newspaper reported that the broadcasters, which had invested millions of pounds in colour technology, were initially apprehensive about the low take-up of colour sets.

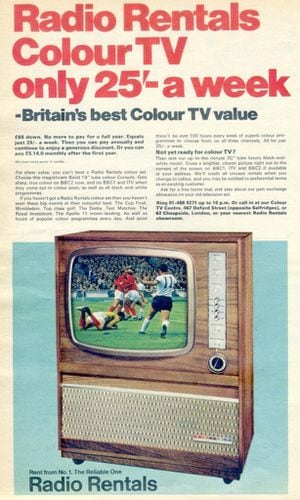

Even by 1969 the cost of the sets – £200 for a basic model, equivalent to 11 weeks' pay for a police officer – put them beyond the reach of the average working man. However, it did lead to rapid growth in the rental market, which meant that it was possible to hire a set for 25 bob a week, with the added bonus that the shop to take care of the repairs and maintenance of these complicated and temperamental devices.

This burgeoning market meant that by 1972 more than 1.6 million UK households had a colour TV, and they soon began to outsell colour sets.

But even after half a century, it seems that not everyone has embraced the colour revolution. Figures from TV licensing reveal that there are at least 29 people across Shropshire – including 13 in Shrewsbury, seven in Telford and six in Oswestry – who are still watching their programmes in black and white. Some people clearly believe in the old adage “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”