Noel and Liam Gallagher, Kylie, Prince - I was mates with all the big stars

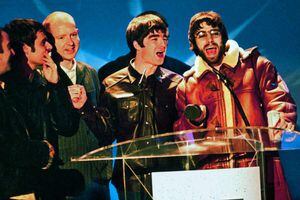

Pick a memory, any memory, just pick one. I don't know. It could be hanging out with Noel at the Brits or carrying a fistful of awards for Liam at NME's Brats.

There were the regular Saturday morning phone calls from John Squire, who talked about his daughter and favourite films rather than the boring old Stone Roses. Perhaps it was the Blur versus Oasis dust-up; Prince's extravagantly designed, lilac-themed dressing room in the bowels of Wembley Arena; Bono's cigars at a theatre dressing room in South Wales; or SexKylie's elegantly-sculpted legs and immaculately coiffed hair in a marquee in Scotland. But no, it wouldn't be any of those.

Maybe it was flying to LA to interview the Chili Peppers, who surreptitiously ruined our photographer's shots by 'revealing' themselves through skin-tight silver shorts; or perhaps it was trying to switch hotels in New York City so that we could stay in The Chelsea, where Sid Vicious killed Nancy Spungen. Or maybe it was the women: Yoko Ono's phonecall; Courtney Love's threat to sue me; or Patti Smith's incendiary and intimate showcase in one of London's Royal Parks.

Perhaps it was hanging out in Ozzy's kitchen, watching bemused as Britain's hardest rock star got on the floor in front of me to do 100 ab crunches while his dogs barked madly; being on telly with KLF; interviewing Green Day for Radio One; or being snubbed by Gary Barlow.

Maybe it was the drugs, the champagne, the tour buses to Glastonbury, the horrific hangovers, the groupies, the American tours, Skinner & Baddiel or Euro '96. Or perhaps it was early morning limo rides to the BBC to talk on the radio about what might be Christmas number one; or the trips to New Zealand, Kansas City, Geneva or Anywheresville. What day is it?

Where are we? Who cares. Let's rock. Or maybe it was going in search of my favourite rock star, the late and still-lamented Richie Edwards; a man for whom the word 'genius' was a fitting description.

But no, we're still not there. It wasn't the gold and plantium discs from Ocean Colour Scene; nor the interview with another hero, a thoroughly pleasant Paul Weller; or the private jet flight with Blur drummer Dave Rowntree – Essex has never looked so good as when you're being flown by the pilot's-licence-holding tub-thumper who beat the skins on Parklife. My abiding memory of the 1990s is none of those things. My abiding memory is this: I was 'there'.

London was the global capital of cool in the mid-1990s. Forget New York, Paris, Bangkok or Milan. Forget LA, Hollywood, Beijing and Rio. None of them mattered. Cool Britannia ruled the waves. Britpop, Terry Venables, Cantona's kung fu kick – they were the highpoints that swept away the miserabilism of grunge and decades of British underachievement.

For sure, the 1990s weren't as cool as the sixties. Oasis and Blur were no Beatles and Stones. And Shed Seven, The Charlatans, Tricky and PJ Harvey were no match for Dylan, Joni, Janis, The Doors, The Beach Boys and Hendrix. But they were as cool as any other decade, either before or since. Nothing Compares 2 the 1990s. Except, of course, the 1960s.

Between 1994 and 1996, I worked at the NME, on the 25th floor of King's Reach Tower, in Stamford Street, before other, glitzier jobs came a-callin'. At dusk, we'd marvel at the Waterloo Sunset, which was more glorious than the vision conjured by Ray Davies in his song for The Kinks. We'd review the singles and decide what you, the listener, would buy the following week. The ones that we didn't like were spun, like Frisbees, into the street below – that's where the promo copy of Sleeper's Inbetweener went.

We'd get drunk at lunchtime then go back to the office and fight over what to listen to on the stereo. We'd go into the office at 12midnight and work through until sunrise, welcoming the cleaners into work. We loved our jobs. Working there was important. NME might as well have been CID – it got its workers access. In the words of Paul Weller, it made them 'someone'.

The 1990s weren't a tea party. One of my bosses was a former bit-part player with rubbish pop band. He'd overcome a severe heroin addiction and renamed himself after a violent and ruthless character in the 1947 movie Kiss Of Death. He was booted off The Culture Show for having a bad attitude and used to thump his desk when people he didn't like tried to call him. It was a testing environment in which to work.

The politics at NME rivalled those in the dark and shady world of boxing. Covers went to bands whose PR slept with people on the paper, tempers flared in debates about OCS versus Mogwai, or Blur versus Oasis. There were cliques, spats, hang-ups and breakdowns – and all in a morning's work.

In one year alone, I consumed between 230 and 250 gigs and spent thousands and thousands of pounds on taxis. My daily diet consisted of Lucozade, B&H, Bishop's Finger (a drink, not a euphemism) and, in a concession to modernity, a toasted mozzarella, basil and sundried tomato panini. There were no drugs, though they were available in industrial quantities had I have wanted them.

Our lifestyles were absurd. We signed up to a nervous-breakdown-inducingly-intense routine of fags-work-red wine-women-booze-ligging-writing- interviewing-taxis-planes-takeaways-writing-and-sleep. Those without stamina were cast aside. The dreamers and schemers were washed up with the flotsam and jetsam of a mad decade.

My time at NME coincided with Britpop. I wrote the Blur versus Oasis front cover, which charted the rivalry of Britpop. The majority of office staff had emerged from Oxford, Cambridge or other well-heeled backgrounds and were in the Blur camp. A small number of us came up from the streets and what we lacked in finesse we made up for in commitment and craft. We backed Oasis. And we were right.

Meeting people who were caught in a moment provided an education. John Squire became a mate, for instance. He called regularly on Saturday mornings for a chat, telling me about films he'd watched.

Prince was also a remarkable man. He granted five of us interviews before playing a show at Wembley Arena. We were ferried to the venue and given strict instructions: no notepads, no tape records, no pens and no equipment with which to record him. When I asked why, he looked me in the eye and smiled: 'You'll remember what's important'. And he was right. The resulting feature was syndicated around the world and won me an award.

Hanging out with the biggest names was our job. It was work. We weren't star-struck. We got on with it because it was what we did. At the 1996 BRIT Awards, at which Oasis won Best Album, Best Video, and Best Group and earned two further nominations for Best Single, I approached Noel after the show to offer congratulations. He was a decent bloke, one of the best, and we got on well.

He'd given me a world exclusive prior to the release of their defining work, (What's The Story) Morning Glory?.

"When can I interview you next?" I asked, afterwards.

"We're off to America. If you get yourself on the plane, you can interview me then."

So I did. My boss booked me a flight to Kansas and St Louis and I watched Oasis rock the mid-West. In between, I was present at small subterranean concert rooms when Radiohead recorded b-sides, or in studios with The Charlatans, The Chemical Brothers, No Doubt and myriad others.

It's 2013 and the nineties are gone but not forgotten. We Don't Look Back In Anger.