Is Corbyn on right track with rail re-nationalisation?

Stand-up comics' gags about British Rail sandwiches. Sitcom jokes about delayed trains. Tabloid headlines about leaves on the line.

A generation ago, it would have been hard to envisage that one day people would be clamouring for the revival of Britain's unloved national rail operator.

But 18 years since the disappearance of the infamous double-arrow logo, a bandwagon to re-nationalise our railways appears to be gaining traction.

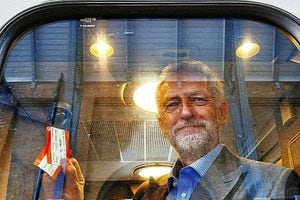

Next week, Jeremy Corbyn will use his first conference as Labour leader to unveil his plans for a piecemeal nationalisation of the rail network, and, it seems, his ideas are not without some support.

More than 37,000 people have signed a petition by a group calling itself Bring Back British Rail, while a recent opinion poll found that 52 per cent favoured the re-nationalisation of the railways. Suddenly, it seems there is a wave of nostalgia for the days of stale sandwiches.

Jeremy Corbyn may think he is tapping into the groundswell of public opinion with his plans to re-nationalise railways.

But it might do him good to revisit the county of his childhood to speak to train users on their daily commuter run.

People at Telford railway station are distinctly lukewarm about the idea – they just want the trains to run on time.

Using the trains to make their way home from the recent Bed Show at the Telford International Centre were furniture agents Charles Hickland, 63, and Gavin Watt, 48.

They live in Belfast but often use the trains in England while going about their business.

Mr Watt said: "I don't think it is a good idea for the Government to be running the trains, they often don't seem to do a very good job of running the country never mind the rail service."

IT worker John Williams lives in Solihull but commutes daily to his job in Telford.

He said: "To be honest, I don't think re-nationalisation will make a huge difference. What it needs is more investment."

Commuter Phil Graham, a father of two from Wrockwardine near Wellington, stopped using the trains regularly a few months ago and began using the buses instead but said he couldn't see it making a big difference to his decision.

Mr Graham, 55, who works in computers, said: "

I don't really remember British Rail but I can't imagine it being any worse. The bus is probably more expensive for me but I prefer it not to have the hassle."

Shrewsbury Sixth Form Student, Phoebe Blythin, uses the train every day to get to lessons from her home in Telford.

The 16-year-old maths, economics and French student said: "The service is fine now. I have a season ticket which helps with the price."

Former Shropshire schoolboy Mr Corbyn, speaking ahead of the conference in Brighton, says: "We know there is overwhelming support from the British people for a People's Railway, better and more efficient services, proper integration and fairer fares.

"On this issue, it won't work to have a nearly-but-not-quite position. Labour will commit to a clear plan for a fully integrated railway in public ownership."

Interestingly, the Yougov poll suggests that support for rail nationalisation is an emotional and ideological response, rather than a pragmatic one. The people who took part were given three choices: would they like to see the railways privately owned, nationalised, or "whichever maintained the highest standard".

The third option proved the least popular, being supported by just 14 per cent of those questioned. In other words, regardless of which side of the fence one sits on, our views are more likely to be shaped by political ideology

When former prime minister Sir John Major oversaw the privatisation of the railways in the 1990s, his dream was to recreate what many saw as the golden age of rail, when proud regional companies such as Great Western Railway and London, Midland & Scottish battled for customers, managing and maintaining all aspects of the service. However, civil servants persuaded him to adopt a different model, where a separate company, Railtrack, would be responsible for managing the rail network, leasing routes to different companies.

This new model was much criticised at the outset, not least because of the legal costs of complicated contracts between Railtrack and the many train-operating companies. The original model did not last long. Railtrack ran into financial difficulties, and Tony Blair's Labour government effectively nationalised it, replacing it with Network Rail, a state-owned company.

It might be argued that the Blair government's nationalisation of the network itself was as much a political decision as the original privatisation. There was never any suggestion that privatisation would put mean an end to taxpayer subsidies for rail travel.

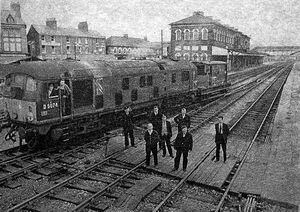

No major rail network in the world operates without subsidy, and critics of privatisation point out that government spending on the railways has tripled in the 20 years since privatisation. But supporters argued that a privatised rail network would be better than the old British Rail, which had become a byword for inefficiency, and that it would also lead to greater investment in the network.

There are some figures to back this argument up. Between 1960 and 1995 passenger numbers fell by a third (from around one billion a year to just over 600,000). Since privatisation, passenger numbers have more than doubled to 1.6bn.

There are claims too that there has been record investment in the railways, improving services and safety. The current rail minister, Claire Perry, argues that the railways are enjoying the largest programme of investment since the Victorian era. On the other hand, it might reasonably be argued that the state ownership of the railways coincided with a time of huge expansion in private car ownership, a period when people would have been turning away from rail travel regardless of who they were owned by.

Equally, the growth in passenger numbers in the past 10 years, and the increased investment, may simply be a reaction to road congestion, rising fuel costs, and people travelling further to work than they may have done in the past.

Economists Eamonn Butler, of the right-leaning think-thank The Adam Smith Institute, has branded Mr Corbyn's plans "dismal".

"The public is better served by an independent regulator scrutinising private providers than a nationalised industry responsible only to ministers and Parliament," he says.

"The independent regulator can fearlessly point out when things are not up to standard. The minister, being responsible for the provision of the service, will never admit to failures."

He also argues that a new nationalised railway would suffer from lack of investment, as it would need to compete for funding with more politically sensitive areas such as the NHS or education.

He says: "The old British Rail did not make profits at all, indeed, it made a large annual loss. It was inefficient and vastly overstaffed

"A nationalised industry has to compete for investment with other government departments and services. Spending decisions owe more to the political necessities of the moment, like elections, than long-term investment strategy.

"Second, politicians fear that cutting staff costs causes them political problems, while cuts in capital investment are barely noticed: the service just gets slowly less reliable."

Mr Butler also says that a lack of competition in nationalised services gives huge strike-threat power to the staff, yet leaves service users with no power take their custom elsewhere.

"Lack of competition means there is no pressure to change, to adapt to customer needs, stay up to date, modernise and cut costs," he adds.

Britain's railways were first nationalised in 1948, under Clement Attlee's postwar Labour government. But a fall in passenger numbers and heavy losses led to Richard Beeching being appointed to rationalise the services. Lines were scrapped and hundreds of stations closed. During the 60s, 70s and 80s British Rail became notorious for its slow services, industrial action, poor catering, and ageing rolling stock. It did not start keeping punctuality figures until 1992.

However, one of the reasons why there appears to be so much support for re-nationalisation may be down to the fact that since 2010 the Government has been trying to shift the burden of running the railways away from the taxpayer and on to the passenger.

Back in 2010, 51 per cent of the costs of running the railways were borne by passengers, now it is 62 per cent, reckoned by some to be the highest rate in Europe.

That change has been brought about by the Government insisting that regulated fares be increased by more than the rate of inflation. Rail unions, which support re-nationalisation, point out that such fares have risen by 25 per cent in the last five years while average pay has gone up by only nine per cent. Unsurprisingly, this has antagonised commuters, especially those who still can't get a seat on rush-hour train.

The Government has attempted to respond to this by restricting regulated fare increases to the rate of inflation for the next five years. Such fares will go up only by one per cent next January, and this at a time when pay increases are exceeding inflation. So commuters should feel less stretched. Yet campaigners for re-nationalisation have struck a chord with their claim that all that privatisation has led to is increased fares for the poor, long-suffering commuter and increased profits for the rail companies.

Under Ed Miliband, Labour went into the recent election with a policy that fell far short of re-nationalisation. Instead, they proposed legislation to allow public-sector operators to "take on lines and challenge the private train-operating companies on a level playing field".

This policy followed on from the 2009 takeover of the East Coast Main Line by the publicly-owned East Coast company, which was formed as an operator of last resort when National Express was refused further financial support and lost its franchise. The franchise returned to private ownership this year when it was taken on by Virgin East Coast.

Mr Corbyn's plan is likely to be to wait for the present franchises to expire, and then award them one-by-one to a new state-owned operator. Some five out of 16 franchises are due to expire between 2020 and 2025. So, in the event of a Corbyn victory at the next General Election, commuters could expect to see significant changes in a short period of time.

However, Ukip's transport spokesman, the Shropshire Euro MP Jill Seymour, suggests there might be another spanner in the works. She says that as long as Britain remains a member of the European Union, it would simply not be allowed to follow such a policy.

"Ever since the first Railways Directive back in 1998, the EU has dictated that all member states must provide competition and allow independent companies to apply for non-discriminatory track access," says Mrs Seymour.

Supporters of rail nationalisation will doubtless argue that the governments of France and the Netherlands have managed to find ways around these laws.

However, the Rail Delivery Group – which represents train operators – claims customer satisfaction for punctuality, train frequency, information and station cleanliness, is higher in the UK than in France, Germany and the Netherlands. It claims that when rail franchising was introduced, British Rail was running at a £2 billion-a-year loss in day-to-day-costs but today, it virtually covers its running expenses.

Certainly, there are many who say those arguing for rail nationalisation possess a short memory, and forget just how unpopular British Rail once was. Indeed, many of the younger supporters of nationalisation probably have little, if any, real memories of the old British Rail. There is also an argument that many of the complaints about delays and disruption to services, relate to Network Rail, which is already nationalised. Only last month, Network Rail was was fined £2 million by the rail regulator for "inept timetabling and poor planning for upgrades".

And it was cost overruns by Network Rail which this year caused the Government to pull the plug on various major investment projects in its £38.5 billion five-year plan. Network Rail's debts have also risen by £5 billion over the past year, and now stand at £37.8 billion.

It seems there are concerns among some in the Labour Party that the public mood could quickly change when the policy is put to the test.

One party source says: "A lot of people like this idea, but the worry is that things could get worse if they are brought back into public ownership.

"All it needs is for public money to be diverted somewhere else and we could end up facing some very difficult questions."

l Should our railways be re-nationalised? Vote at www.shropshirestar.com